The Everest Effect: Adventurism, Ego & The Commodification of Experience

Adventurism is defined (per Google anyway) as the willingness to take risks; actions, tactics, or attitudes regarded as daring or reckless.

So when Scott Carney, investigative journalist, anthropologist and author of What Doesn’t Kill Us, decided to jump into the deep end of a Reddit AMA (Ask Me Anything), he really put the philosophy espoused from his latest book ‘The Wedge’ to the test.

Things didn’t go so well.

In actuality, things don’t typically go so well for Scott when he hosts an AMA, and this hadn’t been his first Reddit rodeo.

While it’s not necessarily anything new of a trend to see such cynicism directed at the hosts of Reddit AMA’s, it’s sometimes possibly indicative of something more. Sometimes. Possibly.

I began sifting through the litany of scorns and insults, trying to pick up on something that ran deeper than the usual trolling, judging and unproductive chastising.

For it had only been two days prior that I myself had interviewed Scott about his book and found him to be a generally likable guy — in my very limited interaction with him anyway. Hearing him on podcasts and reading some of his material only served to validate my initial assumption.

Nevertheless, I had been drawn in to his timely participation in this Reddit forum, finding it to be a great way to gain further insight into the nature of my article, which simply served to highlight his work on the potential which rests hidden in our neuro-physiological states of consciousness.

The negativity directed at Scott had me roped in. While some comments accused him of over-sensationalizing his work or being too egotistical (the usual critique directed at authors of such content), nothing really stood out as warranting the seemingly excessive sense of intense dislike towards not only his work but of Scott himself.

Then it happened — I ran into a particularly insightful comment which seemed to clarify some of the smoggy and disorganized sentiments directed at Scott, both unifying the fierce dislike and poetically weaving together a purpose behind the collective dismissal of his work.

For the sake of confidentiality at the request of the comment-originator, I’ve chosen to not publish their name nor their Reddit handle, simply referring to them as T.W. Their comment, nevertheless searchable on Reddit, consisted of the following:

“…It seems like you approach life as an accumulation of experiences, notably experiences that can’t be attained by average people with kids, jobs, health issues etc. Is this not just like the accumulation of any other commodity?

Do you see any downsides to treating experiences as commodities to accumulate? I also note the exoticism of the experiences — Latvian “shamans,” ayahuasca — do you notice a specifically western, imperialistic approach to what you’re doing (“the globe has been explored already, but I can still explore and commodify [for sale in a book, at that] my exotic, cosmonautical experiences!”)?

To be blunt, this all seems like the product of an ADHD culture that fetishizes the accumulation of exotic and thrilling experiences. I am much more impressed by someone who can enjoy sitting quietly, or a good book and friends, or who brings mindfulness and this “wedge” to his interpersonal relationships.

— “T.W.”

Naturally, such a well-thought out comment garnered an immediate surge of support from the thread, with Scott himself acknowledging the validity of the critique:

“Thanks for this well thought out question. And it’s a valid critique. But I also find a great deal of solace in ordinary moments. Most of my life is made up of ordinary moments. Hell, I’m still in my pajamas as I type this comment. The reality is that it’s all about contrast between stress and release. Between sympathetic and parasympathetic. Fight and flight and rest and digest. And most people in the modern world don’t get variation.”

— Scott Carney

It didn’t really end there. Both T.W. and Scott dove deeper into the subjects of ego and the commodification of experience — something that seems to be happening all around us but isn’t really acknowledged until things funnel through a breaking point in the more peculiar parts of the internet.

We see it happening at an eye-rolling fervency that still draws us in beyond the point of questioning — this blend of egotism, sensationalism and commodification of experience and adventure; capitalizing off of ‘firsts’, off extreme activities or personal achievements that have been socially diluted to the point of losing any sense of subjective catharsis.

We’ve grown aware of this exploit, which has consequently led some of us to be spiteful of certain social icons and figures who make the impossible happen — dragging such ‘inspirational’ figures over the coals of criticism for their apparently self-serving ambitions.

A suitable current case study is that of endurance athlete and motivational speaker Colin O’Brady, who has recently spurred controversy over his crossing of Antarctica after a National Geographic investigation led to an aggressive questioning of O’Brady’s achievement and a 16-page response letter penned by O’Brady himself calling for the article to be redacted.

“The article, titled, “The Problem with Colin O’Brady,” sought opinion from both travel safety experts and extreme explorers, and left the heavy impression that O’Brady had embellished his achievement to help build a brand (he is now a sought-after motivational speaker).”

— National Post

Like it or not, O’Brady encapsulates this supposed problem of egoism and the commodification of adventurism — if he didn’t, there wouldn’t be any controversy. Regardless of whether he is or isn’t egotistical and whether he does or doesn’t seek to break world records for the sole purpose of capitalizing off of these experiences, there is a brand to be built and a profit to be gained — unequivocally. To argue his true motivation is a moot point.

Now, is this any different from, say, an Olympian athlete who is showered with praise and never questioned on their motivations — which do remain purely competitive and, possibly in consequence, equally egotistical?

The Olympics, along with countless sporting leagues or the entertainment business itself — they too are guilty of commercializing experience, whether that experience is a special moment in sporting history, a dramatic Hollywood reenactment or a comedic act. In fact, it can be said that our entire culture is guilty of it — this is what we’ve chosen to signify as valuable, entertaining, inspirational; in doing so, we’ve created profit streams and revenue systems around this particular exploit. So can we really scorn individuals like O’Brady or Carney for trying to carve out their own profits?

There’s something about the individual exploitation, as opposed to the systematic, which doesn’t sit as right. As T.W. further posed to Scott, the distaste emanates from what he called, the unnecessary ‘philosophical destructiveness’ of Scott’s approach, especially when it comes to sensitive facets of our existence like spirituality or natural resources.

"Regardless of how you personally feel about the above, do you understand how pushing for more and more extreme external stimuli can be destructive? For example, you are contributing to the commercialization of a spiritual native experience — the ingestion of ayahuasca — to sell books. Would you feel any personal responsibility for the commodification of this spiritual native ritual when Western tourists who have read your book turn the ritual into just another festival drug experience?

Do you understand or think about the possible philosophical destructiveness of your approach? I notice from your twitter that you have posted multiple times about your book reaching the #1 spot on bestselling anthropology books. It seems like the drive to be Number One, to have the MOST intensive experiences, to cultivate the “Wedge” to the FURTHEST of its potential, is a very pernicious undercurrent of our society… It fuels the drive for maximal exploitation of natural resources, maximal growth, etc. Can’t we just chill out and stop chasing things to their extremes?

…Don’t you feel like we should, I don’t know, get over ourselves?

— T.W.

In truth, qualities like competitiveness and egoism have greatly helped us get to where we are today — the sky scraper feuds of New York, the space race, even the global rivalry to be more socially-righteous (see national suffrage and same-sex marriage movements). But such egoism has also led to, as T.W. stated, a great measure of destruction; maybe not the kind of destruction that is always ostensibly obvious but often indirect and subtle, with farther-reaching ramifications.

We need not look father than prolific Mount Everest — once a majestic, locally sacred and imposing mountaintop that has fallen victim to the exploits of adventurism and social media feeds; thankfully, it has now become trendier to go and clean the degraded mountain than it is to climb it.

As mentioned, this Everest Effect need not be physical in nature, as it can provide just as much ideological damage — the negative effects of the tourist industry throughout Nepal; the sentiment of conquering nature rather than symbiotically co-existing with it; perpetuating idea that money (hired guides) equates to accomplishment.

The children whom Colin O’Brady speaks to when he embarks upon his motivational lecture circuit — do they begin to idolize his expression of limitless personal achievement or do they confuse it with trying to replicate his social media following; do they realize that they too can seek control over their inner doubts or that they too can seek similar personal, social and financial exploits?

It goes without saying that the commodification of experience and the ego underlying such an effort are nothing new to our world. While they’ve perhaps been exacerbated by the advent of social media and trending concepts relating to variable forms of self-actualization, they nonetheless fall under the realm of the celebrity effect.

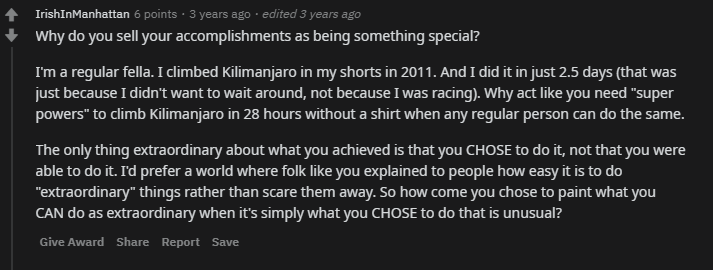

So it was hard for me to still chip away at a comprehension of why the efforts of people like Scott Carney resonate so negatively with many people. His take? As he told me on a side chat during his AMA, the simple fact is that to get people's attention on the internet, something sensational is needed - the title, the experience, the science.

Scott acknowledged this ever-present need for sensationalism as a by-product of the business and the apparent energy-cell behind this problem in the first place.

It’s the need to sensationalize, the need to dramaticize — this is what builds a brand and what sustains it. This is what both fuels criticism towards those sensationalizing their lives and fuels those lives in the first place. This is what elevates the people of Nepal through a profitable tourism industry but ruins Mount Everest.

All in all, this is the product of a consumerist culture that, as T.W. phrased, fetishizes the accumulation of exotic and thrilling experiences. It’s ultimately up to us if we want to partake in it — as spectators, as active constituents or as critics.

As a caveat, it may be worth asking: is it fair to criticize? On a personal, one on one level (or thousands versus one — as Scott Carney seems to almost enjoy), it doesn’t seem so. On a collective level, it helps to appreciate what’s really happening: we as a collective organism are criticizing ourselves as we continue to evolve, and we may or may not become tired of the pitfalls which accompany such a consumerist way of interacting with one another.

It ought to be underscored that this isn’t just Scott Carney or Colin O’Brady — it’s the product of a culture that is the product of a species that takes a long time to figure itself out — if ever at all.

So until the criticisms stop accumulating like the commodification of experiences themselves, we apparently have long ways to go before we strike a proper balance that everyone seems to agree on.

Or maybe that’s just not possible.

To close on the words of Seneca, a quote also to be found amongst the many exchanged words of the above-mentioned Reddit thread:

“You are not responsible for your first thought.

You are responsible for your second thought and your first action.

That is where your power lies.”

— Seneca

Image courtesy Martin Jernberg

Original interview with Scott Carney to be published in a forthcoming article.